FOUND IN B.C.? Yes. Recently confirmed in the Salmon Arm reach of the Shuswap Lake. Also known from the Pend d’Oreille, Pit, Coquitlam and lower Fraser rivers.

Freshwater clam shells are round to triangular in shape with distinct concentric ridges.

Identification

Freshwater clams (Corbicula fluminea), sometimes referred to as Asian, golden or pygmy clams, are a freshwater, filter-feeding bivalve originating from southeast Asia. The shells are generally a pale or yellow-ish brown but can sometimes be quite dark, and typically grow around 2.5 cm in size (although they can grow up to 6.5 cm). The best distinguishing feature of this shell, from other bivalves found in B.C., are the distinct concentric ridges on the shell (which is slightly round to triangular in shape).

Life Cycle

North American populations of the freshwater clam are hermaphroditic. This means that they are capable of self-fertilization and a single individual has the potential to start a new population in a new waterbody.

An adult clam can release up to 70,000 veligers per year over several reproductive events (McMahon, 2002). When an adult clam releases veligers, although small, they are fully developed. When they find a suitable place to anchor, they will continue to grow in size and their high feeding rates allow them to grow quite quickly. Freshwater clams will live for 1-5 years.

Ecology

Freshwater clams are burrowing bivalve, so they require well-oxygenated sediments in their habitat, such as sand mixed with silt and clay. Freshwater clams are suspension feeders that feed on phytoplankton and detritus (decomposed organisms). Similar to zebra and quagga mussels, they have been documented to avoid consuming cyanobacteria. In their native range, Freshwater clams are predated upon by other benthic invertebrates, waterfowl and some fish (e.g. sunfish, carp).

Introduction and Spread

Freshwater clams may have arrived in North America primarily as a food source in the early 1900’s. They have been relatively widespread across North America since the 1950’s, which may be attributed to human-assisted dispersals, including use as food and bait, aquarium trade, transport of veligers in ballast water and transport of adults and/or veligers in digging and dredging equipment and other watercraft. High reproductive capacity and rapid growth rates have led to invasive success and dispersal across the continent by the Freshwater clam.

Freshwater clams have been present in the Lower Mainland region since about 2008. They are currently known in the Pit, Coquitlam, Fraser and Pend d’Oreille river systems and one lake on southern Vancouver Island. Their presence in Shuswap Lake was confirmed in 2020.

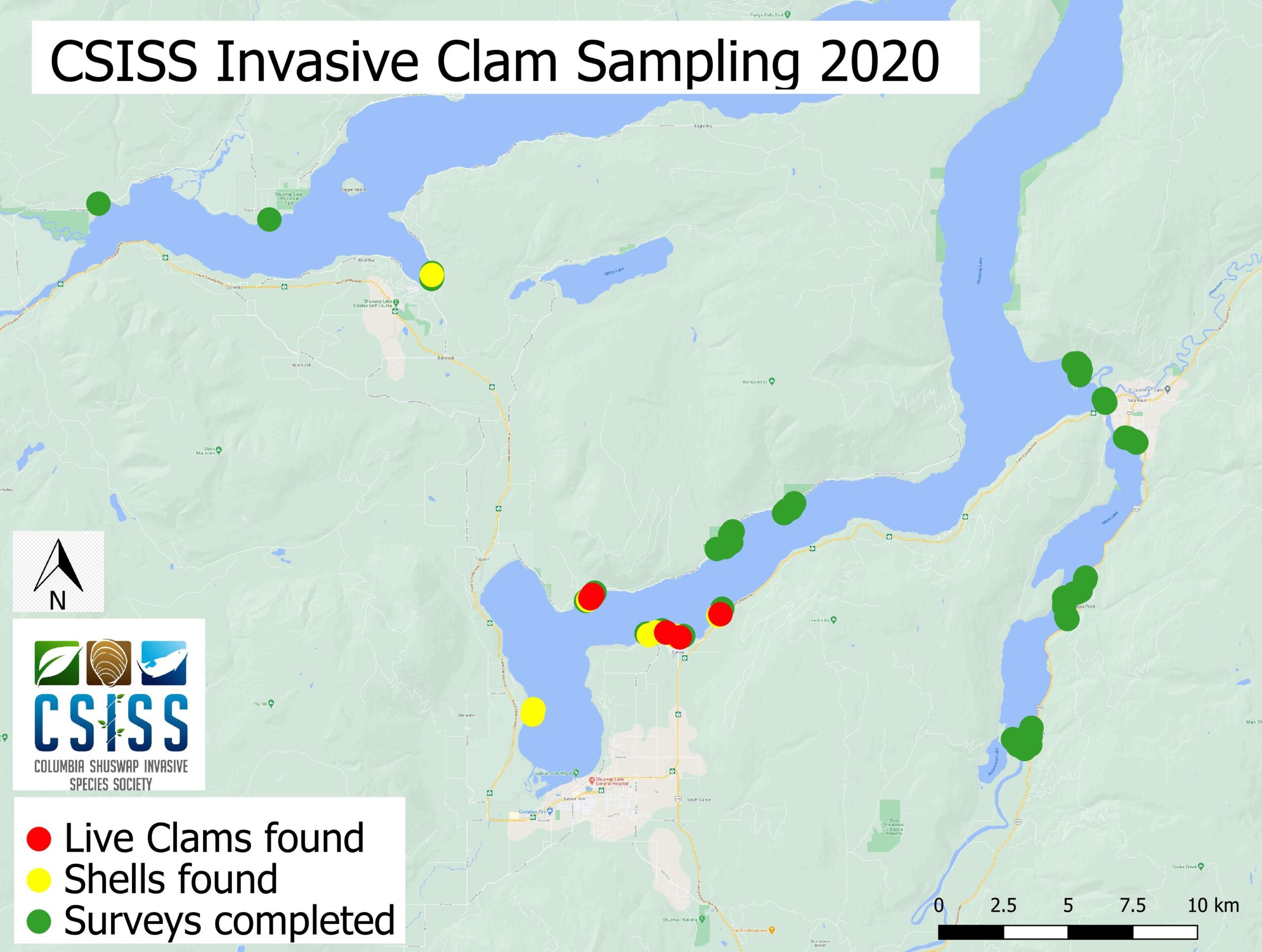

Recent surveys have found invasive clams in the Salmon Arm of the Shuswap Lake

Substrate surveys detected live clams at Sunnybrae and Canoe. Beach walking surveys found shells at Sandy Point. The surveys were conducted by the Columbia Shuswap Invasive Species Society with funding from the Shuswap Watershed Council, direction from the Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship, and assistance from the Invasive Species Council of B.C. job creation program. In 2022, CSISS received reports from that public of shells found on beaches at Herald Provincial Park and Sicamous Beach Park.

Unfortunately, once established, eradication of Corbicula fluminea clams from a complex, connected waterbody, such as Shuswap Lake, is very unlikely and management methods are limited. Impacts to the system are difficult to predict and depend on several factors. The best thing that YOU can do is prevent spreading this species to other lakes and rivers. Clean Drain Dry your watercraft and gear and never release live animals or plants into waterways.

Impacts

Environmental: High filtration rates allow the clams to consume large amounts of phytoplankton which can alter freshwater food webs. This change in the abundance of phytoplankton can trigger inverse responses at other levels of the food web, a phenomenon known as trophic cascade. The removal of plankton can also lead to increased water clarity, which in turn allows aquatic plants to proliferate. Rapid colonization of new areas can overwhelm native species (like floater mussels and pea clams) by outcompeting them for space and food. Freshwater clams are also capable of deposit feeding on buried organic matter which also increases interspecific competition with native pea clams. At extreme densities, freshwater clams can actually alter habitats and effectively displace native invertebrates from the area. Lastly, the clams are able to accumulate toxins in their tissues and pass them on to their predators.

Economic: Similar to many other invasive invertebrates, freshwater clams are well-known for their biofouling properties. They have been reported to cause problems in electric generation and water treatment plants around the world. Their ability to increase sedimentation rates can also cause complications for intake pipes and other infrastructure.

Dead freshwater clam shells in Lake Tahoe

Social: As freshwater clams are capable of reaching extreme densities (10,000 per m2), mass die-offs can occur. These mass die-offs result in accumulation of shells on beaches that produce foul odors. In general, their environmental and economic impacts—altered food webs and fish populations and drinking water quality, for example—will indirectly affect both local residents and tourists to areas which they have invaded.

What Can We Do?

CLEAN DRAIN DRY: Clean off all plant parts, animals and mud from watercraft and equipment (e.g. boat trailers, paddles, fishing gear, waders and boots). Drain onto land all compartments and accessories that can hold water (e.g. bilge, ballast, live wells, buckets) and remove plugs before traveling. Dry the watercraft and equipment before launching into another body of water.

INSPECTION: When travelling into B.C., all watercraft must be inspection and Watercraft Inspection and Decontamination stations. To learn more about what is required when bringing a boat to B.C. visit the Province of B.C.’s Invasive Mussel Website.

DON’T LET IT LOOSE: Never release aquarium pets or plants into the wild. Never discard unused bait into the wild. Be aware of bait restrictions in B.C.

REPORT: Report all sightings of invasive species to CSISS on our website, to the Province with their online form or on the ReportInvasive mobile app.

For more information: Invasive Clam Species Alert

Literature and Resources

Bolam, B. A., Rollwagen-Bollens, G., & Bollens, S. M. (2019). Feeding rates and prey selection of the invasive Asian clam, Corbicula fluminea, on microplankton in the Columbia River, USA. Hydrobiologia, 833(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-019-3893-z

Darrigan, G. (2002). Potential impact of filter-feeding invaders on temperate inland freshwater environments. Biological Invasions, 4, 146–156.

McMahon, R. F. (2002). Evolutionary and physiological adaptations of aquatic invasive animals: r selection versus resistance. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 59, 1235–1244.

Strayer, D. L., Caraco, N. F., Cole, J. J., Findlay, S., & Pace, M. L. (1999). Transformation of freshwater ecosystems by bivalves. BioScience, 49(1), 19–27.

Strayer, D. L. (2009). Twenty years of zebra mussels: lessons from the mollusk that made headlines. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 7(3), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1890/080020

Vaughn, C. C., & Hakenkamp, C. C. (2001). The functional role of burrowing bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Freshwater Biology, 46, 1431–1446.